It was at the age of nine, in 1989, that Samuel Laflamme encountered music through cinema. Too young then to go see Batman in the theatres, he quickly grabbed a VHS copy at the video rental place a few weeks later, but alas, only the original English version was available. His parents would narrate parts of the plot so he could follow the superhero’s adventures, but it was the music that grabbed his attention from beginning to end.

“It’s only much later that I realized the impact it had on my way of perceiving things,” says screen composer Laflamme. “It’s crazy how music can create a whole universe.” Much more interested in his Lego bricks then the piano lessons in which his parents enrolled him, he only developed his interest for screen composing much later. “I would listen to everything that was coming out: John Williams, Alan Silvestri, the music for Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Jurassic Park. . . But I was headed to cégep in science,” he recalls.

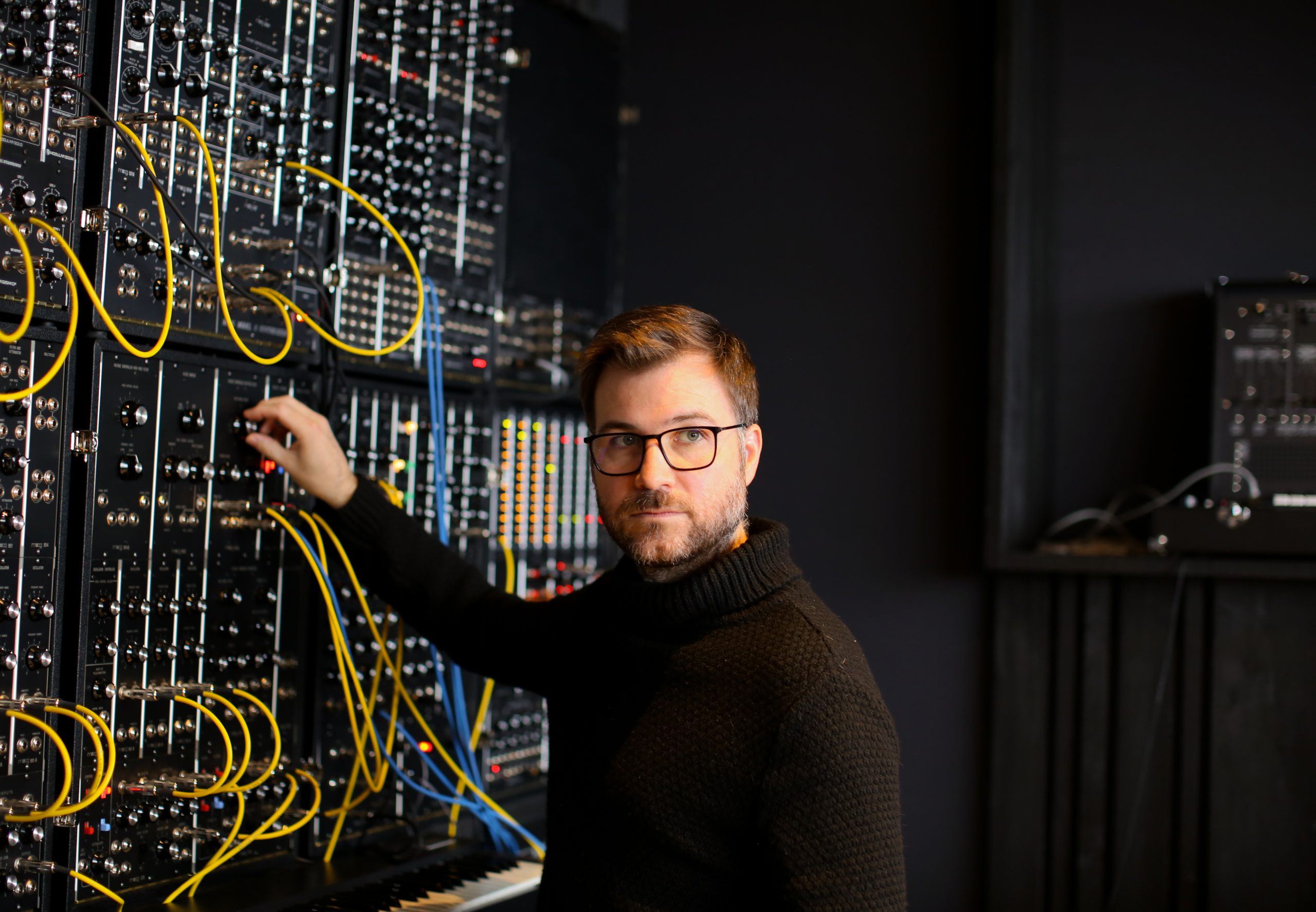

It’s at cégep de Drummondville that he drifted towards music, wanting to create massive orchestrations. Once he enrolled at Université de Montréal and studied under Michel Longtin, he was finally “allowed to answer that calling. It was the beginning of electronic music, and I still wanted to do screen composing. I’d opened a small studio on Saint-Laurent Boulevard and it was there that I met the right people at the right time. There was a lot of post-production being done there, and it was the heyday of specialized cable channels. People needed all kinds of sounds. They took a chance on me.”

It is thanks to his undeniable talent and marked interest in film music that the Institut national de l’image et du son (INIS) extended an offer to teach a class: “I was teaching people who’d done years in the advertising world and were looking to develop their artistic side,” he explains. “In other words, I met a whole bunch of people with a lot of experience and who extended more opportunities later on.” Truly, he found his clan at INIS. His colleagues at Passez-Go are nothing short of a second family for him.

“Pour toujours plus un jour, Le chalet, L’académie, Chouchou. It’s always the same gang. We started together with a tiny, budgetless project over a decade ago, and today we work so well together that we understand each other without having to say a word,” he says. The music he composes for his colleagues/friends are tied to the project right from the pre-production stage. “It allows us to have a common vision, a mutual understanding and a bond,” he adds. “Finding artistic visions that are able to merge so effortlessly is extremely precious.”

Even though his talent shone internationally in 2013, thanks to the music he created for the horror video game Outlast, with these friends he perpetually feels like he’s working without working. Videogames are enjoyable for him, but for different reasons. What he feels really passionate about when composing for television productions is the fact that they’re an integral part of the artistic output taken as a whole. “The commissions aren’t specific, and it’s not like I’m just delivering a project. I’m asked what my vision of the soundscape is, and that input is considered seriously,” he says. His first drama production, last fall’s Québec hit Chouchou, aired on Noovo, allowed him to push the boundaries of this creative approach even further.

“The whole team was having a Zoom meeting,” he recalls. “We were looking at mood boards and the director of photography said he wanted to use lenses from the ’70s to achieve a more organic perspective, a certain softness to the images. That was the spark for the whole team, including me for the music, the costumes, the set decoration, etc.”

Naturally, the direction team came to his studio to listen to Samuel’s jams, which raised questions and evolved alongside the ideas that were pitched. “I was improvising on the piano and without my knowledge, they sent those demos to the editor,” he remembers, giggling. “The confidence level in that team is right up there.”

Asked to come to the set to feel the energy of the series, he had a chat with the main actress, Evelyne Brochu. “Her character is in a relationship with one of her students who’s a minor, and I asked her if she felt her character was unhappy at home, thus explaining why she does such a thing. She said no, and that’s why it was even more shocking when we realize that before she falls for this momentary but forbidden moment of passion, her life is perfect. That’s how I understood that, musically, I couldn’t compose music that had undertones of anger or discontent when she rides her bike, for example. The emotional undercurrent is much softer. That proximity with the team on set completely changed my outlook.”

Click on the image to play the video of Samuel Laflamme’s theme for the TV series Pour toujours, plus un jour

Last fall, Encore Television-Distribution and Passez-Go sold the broadcast rights to the original version of Pour toujours plus un jour to TF1 and TV5 Monde, thus making the series available to several thousand new viewers.

“The end of that series, which delves into death, but mostly serenity about death, truly was the creative spark for Chouchou,” Samuel explains. “In both cases, I think, the music envelops the scenes like an empathetic glance. I spent an enormous amount of time on these pieces, not because they have any kind of virtuosity to them. What takes time is understanding, sleeping on it, digesting the story until you get that ‘Eureka!’ moment.”

Going forward, all Laflamme hopes for is to work with people who want to work with him. “I’m working on a horror movie with fans of Outlast who insisted I compose their music,” he says. “No matter what the project is that I’m offered, I evaluate the possibilities for pleasure.”

The composer, a master at marrying each visual moment to the most appropriate sound possible, is convinced that “people who say film music shouldn’t be heard are absolutely wrong.”